At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards, at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I can only say, there, we have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, Burnt Norton; The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot, Faber and Faber, London: 1969, p. 173.

The sun, moon and planets, like the geometry of forms, were created,according to Plato’s Timaeus, by the Craftsman. Yet before the beginning oftime and form there existed, Timaeus tells us, a formless space. This Chora, as he calls it, was the nurturing uterus of every generation and the catalystfor nature’s metamorphoses – for water to become earth and for air to becomefire. This invisible and formless receptacle of all was The Mother.

The sun, moon and planets, like the geometry of forms, were created,according to Plato’s Timaeus, by the Craftsman. Yet before the beginning oftime and form there existed, Timaeus tells us, a formless space. This Chora, as he calls it, was the nurturing uterus of every generation and the catalystfor nature’s metamorphoses – for water to become earth and for air to becomefire. This invisible and formless receptacle of all was The Mother.

For the French Bulgarian philosopher, Julia Kristeva, the Chora is a soft sfumato essence created when the mother’s body merges with the child. It is a polymorphous undifferentiated state, without distinction between subject and object, “same” and “other”, infant and mother. It is the semiotic moment before words and images, before language, naming and the paternal law – a state that some Buddhists call “the unconditioned mind”. It is a moment before separation and renunciation of the maternal, before the Oedipus complex severs the child from the mother and before castration, as Kristeva puts it, puts the finishing touches on the process of separation. As a space pulsating with primal energies, anarchic impulses and sensory spasms, this mother-child Chora is like Plato’s time before time, space before space, before the imposition of order by the Craftsman. It is like a still point in the turning world, a momentary suspension of phallocratic reference points that is feminine and timeless. This is what the still point means for Melissa Coote.

For T. S. Eliot, the still point entailed suspending time by “playing dead” like “Old Possums”. For Melissa Coote, it can occur during active meditation and transcendental contemplation or at the sudden break in time imposed by the petit mal. It is also summoned-up by Melissa Coote’s “Dropped Hand”: It can be a moment between workday demands and a gap between everyday pressures. This space in-between consciousness is, for Melissa Coote, neither a place of bewildering confusion nor a deathlike wilderness, but one of nurturing peacefulness. It is a space where she can explore her hidden visceral body and plummet its corporeal depths, not skim its fleshy surface. It is a space where she can respond to the vague and shifting calls stirring within her body, listen to its music and dance to its rhythm. It is a space where she can excavate wordless emotions repressed in memory leading back to the Chora. It is a space where she can let her mind float uninhibitedly to discover a language of marks and gestures emerging from her body as a woman. From this still point, she generates her series of paintings.

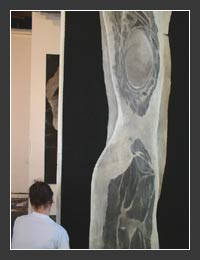

While priming her canvas in whites, Melissa Coote boils the stones of summer fruits until they are whittled down into black soot. Mixing gum resin and glues with these jet blacks, blacker than any packaged pigment, she begins to build-up her surface, layer upon layer. She then strips it down. Through rubbing, scrubbing drilling and erasing parts, she reveals an underlying form. While this form seems to grow and glow like stars and planets in the night-sky, it nestles within the blackest blacks, which gently envelop it like a crucible of velvet, rather than constrain it in a metallic contour. After she rebuilds the form, sanding it repetitively until it becomes like bone, she then veils it with resin and pigment. The spectator must then engage in a similar procedure to glimpse the form beneath the veils.

Amorphous, indeterminate and deliberately incomplete, her shapes and forms do not have an identity that is fixed, immutable and finite. In her language of evocation, not description, ambiguity not certainty, she eludes to the skull of a wombat, the skeleton of a whale, the vertebrae of a snake, the face of the Muse, the hand of a human, the vulva and the vagina. While each Series may appear different, they all grow out of one another. As Melissa Coote explains: “Each of my works feeds off the preceding one morphologically.” Her Series also seem bound by a common morphology through which she is able to allude to the remnants of nature and the experience of woman simultaneously. Just as the snake sheds its skin, so woman sheds the lining of the womb every menstruation. While the whale bones, wombat skulls and snake vertebrae appear to convey archetypes from nature and evolution at its primordial stage, they also resonate with the female pubis, the uterus, the womb and the ovaries. Their lunaresque luminosity and crateresque crusts invoke both the waxing and waning of the Moon around the Earth and woman’s twenty-eight day oestrogen cycle. Although the skull and the skeleton signal death while the hand and the vagina embody the opposite, they are all an integral part of the cycle of life, death and rebirth intrinsic to woman’s body.

Yet the woman’s body from which she speaks is not merely flesh nor fleshness, but the perceptually elusive visceral body. The visceral organs, the foetal body from which we emerge, the sleeping body into which we lapse, are regions ineluctably hidden from perception. It is through the function of these visceral organs that the mother and child fuse to form the Chora. Unlike the visible body, the visceral body seems to be invested with its own circuitry and magical power, beyond will and observation and beneath the reach of conscious apprehension and direction. Digestion seems to be accomplished within the visceral body, without intervention. The lived body is literally formed within that of another arising out of viscerality, not visibility. While menstruation and conception emerge from woman’s visceral body, so does birth, through the vagina. It is, as Melissa Coote’s Vagina Series reveals,like a metaphor for the visceral body and the timeless feminine: Hidden, unseen and unspeakable. Yet, as she suggests, it is also our familiar point of entry into the world. As the title of Gustave Courbet’s painting of the vagina makes plain, it constitutes “The Birth of the World”. It is a tacitreminder that while we are not the authors of our own existence, our visible world rests upon a visceral invisibility.

To represent the feminine in other than phallocratric terms Luce Irigaray theorized the need, in This Sex Which Is Not One, for woman to not mimic man, but to speak from her own body. If we don’t invent a language, if we don’t find our body’s language, she urged, it will have too few gestures to accompany our story. We shall tire of the same ones, and leave our desires unexpressed, unrealized. Asleep again, unsatisfied, we shall fall back upon the words of men – who, for their part, have “known” for a long time. But not our body. By revisiting the symbiotic space of the Chora and by meditating upon the still point, Melissa Coote rediscovers what it is like not to articulate in the words of man, but to utter another language – from her own body. In this language, she explores her instincts and visceral urges. She listens to the groans and grunts of her Muses in her dreams and pursues the fantasies and traumas gnawing at her unconscious. She divines the interrelationship between a range of binary opposites: The visceral and the surface body; the permanent and the ephemeral; the animate and the inanimate; the morbid and the healthy; the cadaver and the living body. She also conjures-up a Brahmin world of wordless dimensions, in order to fathom the invisible beneath the visible and to penetrate the unseeable nameless void that began with the Chora.

If it is, according to Confucian philosophy, only through the hidden, unseen and unspeakable that the total interpenetration of body and world can be realized, if it is only through recognition of the visceral that Neo-Confucian philosophers such as Wang Yang-Ming say that the human body can unite with the universe, then Melissa Coote’s timeless feminine indicates

how this process may begin.